Imagine receiving hundreds of new referrals.

Imagine growing your practice by 50% to 200% over just a few weeks.

Imagine helping thousands more patients each year.

These kind of results are not just possible, but they are highly likely.

But only for those providers and healthcare executives with a critical skill set.

In fact, this skill set may define practice success or failure in the evolving US healthcare system.

The US healthcare reimbursement environment is rapidly shifting away from “fee-for-service” and towards alternative payment models.

The shift requires a new set of skills.

One of the most critical is the ability to build an influential value proposition for payers.

The good news is that it isn’t difficult… you just have to know the steps.

In this article, you will learn:

- A 4-step formula to build an influential value proposition for payers

- What matters to payers and how you can generate data that speaks to their interests and needs

- How to use your value proposition to negotiate favorable terms for your business

Case Study: Palliative Care & Payers

In this article, you will learn how to build a value proposition for payers using palliative care as a case study.

Demand for palliative care services is expected to increase with the aging population.

Individual palliative care practices are poised to substantially grow their businesses.

But they may not understand how best to take advantage.

Like many medical practices, palliative care specialists often look to grow their business through referrals from other providers.

They schedule lots of meetings with oncologists, pulmonologists, cardiologists and other specialists to ask for referrals.

But this approach can be frustrating and have limited success due to:

- Misbeliefs that palliative care provides only hospice care

- Provider “turf wars” and concerns about losing “control” over patients’ care plans (i.e., competition)

- A few referrals each from multiple other providers (i.e., minimal return in exchange for substantial effort)

In short, it can be difficult for other providers to appreciate the value palliative care offers their business. It can be difficult for them to identify shared goals.

Now imagine a different way…

What if palliative care specialists asked for referrals from payers instead of other providers?

After all, payers maintain access to hundreds of providers and hundreds of thousands of patients.

A palliative care practice could be overwhelmed with referrals within days with the right payer contract.

In order to make that vision a reality, we just need to know how to make a convincing case to payers.

I’m going to walk you through the process to do just that… how to build a palliative care value proposition for payers.

What is Palliative Care?

Let’s start by sharpening our understanding about palliative care.

Palliative care is commonly confused with hospice.

I know because I missed this myself after working in healthcare for over 16 years.

I viewed palliative care as equal to hospice care. I misunderstood right up until the time I had the pleasure of meeting a true specialist in palliative care.

This physician specialist set me straight.

He described to me how palliative care ideally gets involved just after a life-threatening diagnosis (i.e., cancer, congestive heart failure [CHF], or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]).

He informed me that palliative care is supplemental to the core care team.

He told me how palliative care assesses patient and family preferences, and then uses those preferences to drive decisions throughout the care continuum.

And what I heard struck me!

I immediately appreciated the potential for palliative care to deliver substantial value to payers.

I saw how palliative care has the potential to impact the entire patient journey after diagnosis.

I saw how palliative care helps plan treatment and non-treatment decisions before patients and families are faced with them.

I saw how maximizing quality of life (QoL) is emphasized more than in many other disciplines.

I saw how palliative care planning is founded upon the preferences of the patients and families.

The definitions provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Webster’s show the greater breadth of palliative care over hospice:

WHO definition of “Palliative Care”:1 WHO. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed August 2016.

Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.

Webster definition of “Hospice”:2 Webster’s Dictionary. Hospice. Available at: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hospice. Accessed August 2016.

A place that provides care for people who are dying

How to Build an Influential Value Proposition for Payers

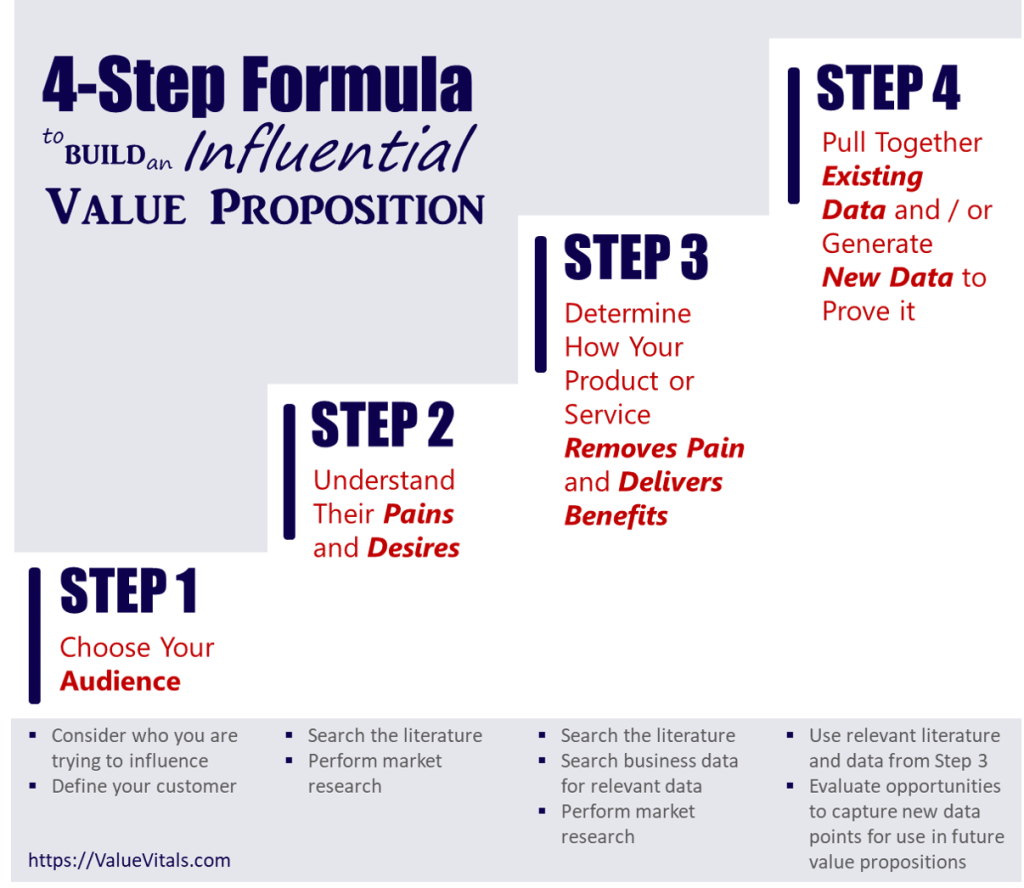

Here is a general 4-step formula for building an influential value proposition. We will use this formula to build our palliative care value proposition:

Step 1. Choose Your Audience

In Step 1, we ask questions like, “who is our customer?” and “who are we trying to influence?”

In the case of the palliative care value proposition, we’ve already determined our audience is payers. Of note, this audience includes other population health management groups such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) or Integrated Health Delivery Networks (IDNs). Our audience is any organization that makes decisions for populations of patients rather than individual patients.

Step 2. Understand What Payers Care About

In Step 2, we want to make sure we understand exactly what payers care about.

We want to know what pains payers experiences and what benefits they desire.

In general, payers care about the following:

- High healthcare resource utilization (HRU) (i.e., healthcare that costs them a lot of money)

- Satisfaction ratings provided by their members

High HRU

So what things cost payers a lot of money?

Some of the biggest line items for payers include hospitalizations and emergency room (ER) visits.

Of course, these are necessary in many cases. But payers know they pay for a lot of avoidable hospitalizations and ER visits.

Furthermore, certain medical diagnoses are associated with relatively more of these kinds of expenses. Cancer, CHF, and COPD are near the top of the list. These medical conditions tend to be life-threatening. As such, they are associated with high levels of morbidity (i.e., sickness requiring a lot of HRU) and mortality.

And that’s where the alignment of palliative care with payer interests becomes almost magical. After all, palliative care is focused largely on intervening with this very population.

As such, we will include high HRU in our palliative care value proposition.

Member Satisfaction

What about satisfaction ratings?

Why are these important to payers?

First, high satisfaction ratings for any business generally mean more repeat business and referrals. That’s true for payers, as well.

But perhaps more important are satisfaction requirements set by government and private organizations. Medicare has established metrics for member satisfaction ratings. Payers must meet or exceed these goals in order to stay on Medicare’s payroll.

Similarly, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) establishes member satisfaction thresholds. Health plans must meet these standards to earn the NCQA “seal of approval.” Payers want this accreditation. This seal helps them sell more to their customers – the employers.

Figure 1. Illustration of a National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Accreditation Seal

Member satisfaction should also be part of our palliative care value proposition for payers.

Step 3. Determine How Palliative Care Impacts Healthcare Resource Utilization and Member Satisfaction

Now we are ready to determine how palliative care truly impacts these metrics that matter to payers.

We anecdotally recognize the value palliative care offers. Our patients and families tell us frequently. But we need proof for our palliative care value proposition.

ASIDE: This is a core issue with most medical practices. They rely heavily on their own anecdotal evidence of the quality care they provide each day. However, the need for proof with real evidence is increasing dramatically. In fact, such proof is now required for payment within emerging alternative reimbursement payment models.

There are three main routes to getting proof we need to develop our palliative care value proposition:

- Literature search

- Local data search

- Market research

Literature Search

The first route to gathering data for our palliative care value proposition for payers is a search of the literature.

The literature search reveals many helpful data points. Palliative care is associated with:

- reductions in resource utilization and costs during hospitalizations3 May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff Millwood. 2016;35:44-53 4 Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855-860

- reductions in ICU utilization5 Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855-860

- reductions in the use of aggressive treatments6 May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff Millwood. 2016;35:44-53

- improvements in quality of life7 May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff Millwood. 2016;35:44-53 8 Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855-860 9 Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721-1730 10 Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. Emergency department–initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. Epub 2016 Jan 14

- improvements in symptom management11 Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721-1730

- improvements in survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and advanced cancer12 May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff Millwood. 2016;35:44-53 13 Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855-860

- increases in documented resuscitation preferences14 May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff Millwood. 2016;35:44-53

- improvements in depression15 May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff Millwood. 2016;35:44-53 16 Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855-860 17 Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1310-1315

- improvements in prognostic understanding18 Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616-1625 19 Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early … Continue reading

The conclusion from our literature search is compelling. Palliative care positively impacts factors payers care about.

We gain further validation from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER).

ICER is an independent policy non-profit group. They published their own evaluation of palliative care in March 2016.20 ICER. Palliative Care in the Outpatient Setting. Available at: https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NECEPAC_Palliative_Care_Final_Report_060616.pdf. Accessed August 2016.

Their analysis strongly supports our palliative care value proposition for several reasons:

- ICER has credibility with payers… our target audience is already listening to what they have to say!

- ICER’s process involves a formalized literature review that corroborates our own

- ICER’s process includes formalized health economic analyses payers like to use (e.g., comparative-effectiveness analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis [CEA], and budget impact analysis [BIA])

- ICER’s results and conclusions highly favored use of palliative care services

Here are a few of the key findings from ICER’s analysis:

- The benefits of palliative care are strong for QoL, HRU, patient satisfaction and mood outcomes

- Palliative care may also have benefits on survival, symptom burden, psychosocial, and caregiver outcomes

- Net annual savings per patient receiving palliative care is $11,508 per patient

- Estimated budget impact of outpatient palliative care programs for a 1 million member health plan for 10% of eligible patients (n=248) results in cost savings of $2.8 million/year

- Assuming 10% of eligible patients enroll in palliative care (78,665), the US system could save $905.3 million over 1 year and $4.5 billion over 5 years

- There is a shortage of palliative care providers which is limiting our ability to realize these cost savings

In summary, the literature review alone provides enough data to build a compelling and influential palliative care value proposition for payers.

Local Data Search

Our literature review findings demonstrate the value of palliative care in general.

But our audience often wants specific information about the value our local practice can deliver.

As such, it is important for us to search our own business practice data that may demonstrate our value.

For our palliative care case study, we first consider aspects of care payers care about:

- QoL

- HRU

- Survival

- Symptom Burden

- Patient Satisfaction

- Psychosocial and Spiritual

- Mood

- Caregiver Outcomes

Through this lens, we ask questions about our own data:

- Do we have patient survey data that asks questions about QoL?

- Do we have patient survey data that captures their satisfaction at different points of care?

- Are we capturing symptom burden data?

- Are we tracking changes in ER utilization and hospitalizations for our patients?

If the answer is yes to any of these questions, we can build the data into our payer value proposition.

Market Research

The last method to determine how our product or service alleviates pain and delivers benefits is market research.

There may be no better way to understand what our customers are looking for than by asking them directly.

For example, we may learn through our market research that payers are particularly targeting non-emergency hospitalizations. Or we may learn a primary focus is to reduce the cost per hospitalization.

While similar, these goals are different enough to change what we highlight in our palliative care value proposition.

For the non-emergency hospitalization goal, we could demonstrate how we reduce treatment-related adverse event (AE) hospitalizations. Our palliative care service for cancer patients includes frequent patient contact that manage AEs and avoids unnecessary hospitalizations.

For the cost per hospitalization goal, we could demonstrate how we reduce length of stay. Our palliative care service actively coordinates with family and outpatient services so patients are discharged earlier.

If we have contacts in payer organizations, we can set up time to get their answers to our market research questions. If not, there are many market research firms that can access payer networks on our behalf for interviews and surveys.

Step 4. Pull Together Existing Data or Generate New Data to Support Value Proposition

There are two components in the final step of our 4-step formula to build an influential value proposition.

First, we pull together existing data.

Second, we generate new data in support of the value of palliative care.

Pull Together Existing Data

From our literature search and the ICER report, we identified quite a few data points that support the value of palliative care in Step 3.

These data points can be pulled together into a story flow that highlights the value palliative care provides to payers.

The ICER results even allow us to perform our own modelling exercises. For example, we can estimate we’ll save the plan $5,754,000, annually, with 500 referrals (i.e., 500 patients x $11,508 / patient).

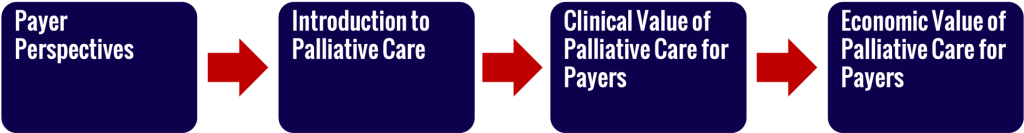

Our story flow outline might look something like this:

Click the “DOWNLOAD” link here to see an example of how the palliative care value proposition “story” can be pulled together in slides:

Generate New Data

We can also generate new data that highlights the value our palliative care practice delivers to payers.

Again, we start with the categories that payers care about. Then we think about how to capture that kind of data.

Table 1. Categories of Payer Interest and Associated Data Capture Methods

| CATEGORY | METHOD |

| Quality of Life (QOL) | Patient Survey |

| Healthcare Resource Utilization (HCRU) | Medical Charts, Claims Data |

| Survival | Medical Charts, Claims Data |

| Symptom Burden | Patient Survey |

| Patient Satisfaction | Patient Survey |

| Psychosocial and Spiritual | Patient Survey |

| Mood | Patient Survey |

| Caregiver Outcomes | Patient Survey |

From the table, we can see that much of our data can be extracted from the medical chart, claims data, and patient surveys.

The medical chart and claims data include data the practice is collecting every day as part of business operations. We only need to know how to query and extract the data we most valuable for our value proposition.

Patient survey data is also relatively easy to capture. We can create paper surveys that all patients receive when they visit our practice. Or, we can use tools like Survey Monkey to generate and deliver surveys to our patients electronically by email.

Drive Business Results with “The Ask”

Once we have built our palliative care value proposition, we are ready to think seriously about our “ask” from payers.

What do we want to ask for from the payer in exchange for the value we deliver?

In the case of palliative care, we might consider the following:

- Higher reimbursements for each claim we submit

- A monthly per member per month (PMPM) stipend to cover palliative care services for a specified target population

- Mandatory referrals within 30 days of diagnosis for a specific set of diagnoses (e.g., cancer, CHF, COPD)

- Partnership in a pilot program to quantify the value of the service delivered

Higher reimbursements, monthly stipends, and mandatory referrals will boost revenue quickly. The pilot could provide results that can be used to improve contract terms with multiple payers.

The sky is the limit. The proof provided by the palliative care value proposition gives us more leverage for negotiations than anecdotes. We decide what we want that will help grow our business. That becomes our ask. We have proven the value of what we deliver as a worthwhile investment for the plan. When the benefits we provide exceed the investment required by the payer, the payer decision becomes a “no-brainer.”

Wrap Up: How to Build an Influential Value Proposition for Payers

Building a referral network of providers is a traditional way for any medical practice to build their business.

There is no doubt it is effective.

But it may not be the most efficient… especially in the evolving reimbursement landscape.

The mandate to go directly to the payer to grow medical practice businesses is getting clearer.

In this article, we learned how to build a palliative care value proposition for payers.

We applied a simple 4-step formula to build our influential value proposition that includes:

- Choose your audience

- Understand their pains and desires

- Determine how your product or service removes pain and delivers benefits

- Pull together existing data and/or generate new data to prove it

We have seen how proving our value with data from the literature, our own internal data, and market research gives us new leverage.

The value proposition puts us in the ideal position for better terms in payer contracts. We use data instead of anecdotes to drive better payer contracts that drive better business results.

I hope you found this article helpful and can apply these principles in growing your own practice!

If you have any questions or would like to discuss specifics for your business, please contact me.

References

| 1 | WHO. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed August 2016. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Webster’s Dictionary. Hospice. Available at: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hospice. Accessed August 2016. |

| 3, 6, 7, 12, 14, 15 | May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff Millwood. 2016;35:44-53 |

| 4, 5, 8, 13, 16 | Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855-860 |

| 9, 11 | Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721-1730 |

| 10 | Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. Emergency department–initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. Epub 2016 Jan 14 |

| 17 | Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1310-1315 |

| 18 | Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616-1625 |

| 19 | Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319-2326 |

| 20 | ICER. Palliative Care in the Outpatient Setting. Available at: https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NECEPAC_Palliative_Care_Final_Report_060616.pdf. Accessed August 2016. |