With the right set of skills, everyone can win in healthcare.

Today’s healthcare is expensive, outcomes are subpar, and incentives are misaligned. The system’s growing complexity prevents even the most well-intentioned leaders working in healthcare from hitting their satisfaction and profit goals.

But there is a simple solution that offers surprising results. A secret skill set that empowers them to turn results and impact they dream about into reality. A secret skill set that helps everyone win in healthcare. This secret skill set is a focus on value.

When healthcare leaders learn how to focus all their decision-making on value, they improve nearly every facet of the healthcare system. They stop wasting money, pay for the right things (i.e., “high-value” interventions), and elevate the health of individuals and populations.

Although many are talking about value in healthcare, very few truly have the skill set to do value on purpose. At Value Vitals, we are here to equip healthcare leaders with these skills so they can drive profits, better health, and affordability in healthcare.

In order to do value on purpose, leaders need to focus on building skills in three core areas. Leaders need to know how to Assess, Build, and Communicate value… the ABCs of Value.

In this article, we will:

- Discover how assessing value in healthcare empowers us to decide which interventions are worth it and what healthcare products or services to develop

- Identify multiple ways to build value for new or existing healthcare products and services

- Explore the most effective ways to communicate the value of healthcare products and services

A is for Assess… Learn to Assess Value

The first key skill in doing value on purpose is to know how to assess value.

Without this skill, money is wasted on “low-value” healthcare products and services. Furthermore, “high-value” innovations are underutilized. The best innovations never get the opportunity to deliver the magnitude of individual, organizational, or societal benefits that are possible with broader adoption.

Not knowing how to assess value also hurts those who invent new healthcare products and services. First, these innovators underestimate their competition, developing second rate products from the start. Second, they miss the opportunity to develop products and services that deliver maximum value to their target market.

So why do we live in a world that accepts such a destructive status quo?

In short, it takes effort to assess value. Not a lot of effort. Not a lot of time. But more effort and time than the alternative… which is to focus on price.

Price is easy! We simply look at a price tag. In healthcare, when prices seem expensive the market seeks lower prices for similar interventions and assumes it has discovered value. As a result, low-cost (i.e., cheap) interventions tend to dominate the healthcare landscape.

But there is a big problem with the “focus on price” approach.

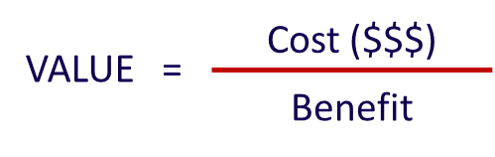

While these interventions cost less up front, often they end up costing much more from a total cost of care perspective. The focus on price up front ignores the many “hidden” costs truly associated with the intervention over time (e.g., side effects). Wisdom says every price should be adequately evaluated by its context. A better way to evaluate healthcare interventions is to assess their value. And price is only one piece of the value equation. Value means we consider the benefits along with the price, simultaneously. In fact, we can write a simple “value formula” to capture the big picture:

Based on this formula, assessing value includes determining our costs as well as our benefits. In other words, we look at price within the context of associated benefits.

So how can we assess value?

The Value Vitals 3-step method for assessing value is:

- Capture price for all components of the intervention (e.g., drug costs, administration costs, monitoring costs, adverse event costs)

- Itemize and quantify all the benefits (e.g., clinical, economic, humanistic)

- Build relevant value equations (i.e., value = costs / benefits)

STEP #1: Capture price for all components of the intervention

When thinking through all costs associated with a given healthcare intervention, it is helpful to start with common categories of costs:

- Medication costs

- Program costs

- Staffing costs

- Fixed costs

- Administration costs

- Adverse event costs

- Healthcare resource utilization costs (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, laboratory)

Within each of these categories, we consider what specific costs are included with the intervention we are evaluating. Some of the costs can be taken right from financial statements (e.g., fixed costs, staffing costs). List prices can often be gathered from vendor sales sheets. Sources such as the CMS Medicare Pricing data 1 CMS. Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data. Accessed … Continue reading and Red Book 2 IBM Micromedex Red Book. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/products/micromedex-red-book. Accessed January 2021 provide list prices for medications.

Other categories such as adverse events may be more complicated. After all, any given intervention (e.g., drug) may be associated with dozens of common adverse events. And these adverse events do not occur in 100% of individuals who receive the drug. Thus, we have to account for a fraction of the costs in proportion to the fraction of how often those events occur for each common adverse event. For example, if 10% of patients on Drug X experience a side effect that costs $1,000 each time it occurs, we attribute $100 to the total cost of care for Drug X (i.e., 10% x $1,000).

STEP #2: Itemize and qualify all the benefits

Benefits in healthcare are commonly expressed in terms of outcomes. The three primary categories of outcomes are clinical outcomes, economic outcomes, and humanistic outcomes (e.g., quality of life [QOL], patient-reported outcomes [PROs], patient experience, function).

Clinical benefits are essentially the favorable health outcomes that result from using a given intervention. Clinical benefits for a diabetes drug may include reductions in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and body weight.

Economic benefits are typically represented by less spending in some area of the total cost of care in a given patient population by investing in a given intervention. For example, an economic benefit of Drug X may be that it results in fewer hospitalization events than Drug Y over a 1-year timeframe. If an average hospitalization costs $10,000, then a $10,000 reduction can be attributed to Drug X’s total cost of care.

Humanistic benefits include improvements in specific measures of Quality of Life (QOL) and function. A humanistic benefit of Drug X may be that it results in higher ratings of function than Drug Y as assessed by the PROMIS® physical functional assessment. 3 Health Measures. Intro to PROMIS®. Available at: https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis. Accessed January 2021

STEP #3: Build a value equation or multiple value equations based on market preferences

Now we get to utilize the information we gathered in steps 1 and 2 to build our value equation(s). Here, we build formulas that give us the insights we are looking for.

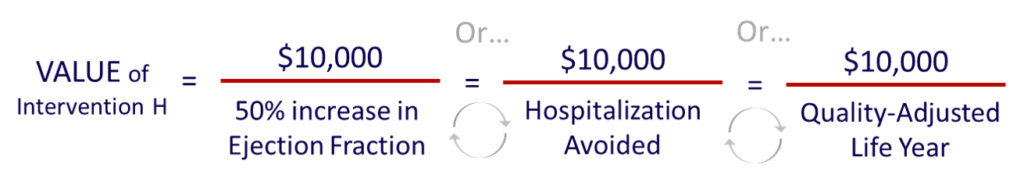

Remember that value is as simple as cost over benefit. Thus, we can start building snapshots of value for our intervention based on their costs and any associated benefits of interest.

Let’s say our hypothetical Intervention H costs $50,000 and has been shown in clinical studies to increase ejection fraction in heart failure patients by 50%. Clinical studies have also demonstrated Intervention H eliminates one hospitalization and increases physical function as assessed by the PROMIS® physical function assessment by 5 points. With all of this pricing, clinical, and humanistic outcome data for our intervention, we can build several snapshots of the value that Intervention H delivers:

At this point, we have multiple ways to consider the value of Intervention H. We get to choose which is most important to us or to our market. For example, the provider perspective may be most interested in the 50% increase in ejection fraction. The payer may be most interested in the hospitalizations avoided. And the patient may be most interested in the positive impact on physical function.

Ultimately, these values are best put into context with other similar interventions to help guide decision-making. For example, if similar Intervention I costs $75,000 per 50% increase in EF, our clear preference is Intervention H.

But what if we don’t have any great data to put in the denominator of our value equation? After all, we can generally get to price… the numerator of our value equation… but there are many times when we do not have what is ideal for the denominator. That’s when we need to know how to create or build value.

B is for Build… Learn to Build Value

The second key skill in doing value on purpose is to know how to build value.

The ability to create value is at the heart of any business. But what does it take to build value in healthcare?

While there are many complicated answers to this question, we can simplify the answer down to a single word. And that word is data. In healthcare data is king. Those products and services that have the best data win!

The Value Vitals 3-step method for building value is:

- Determine what the market values (i.e., what matters)

- Generate evidence using established scientific methods and tools

- Position the evidence against existing interventions

STEP #1: Determine what the market values (i.e., what matters)

It may seem obvious, but few make the effort to really understand what the market is looking for. Ideally, we understand a very painful problem that needs a solution. In healthcare, we often know this as the “unmet needs” in a given therapeutic area. Our proposed solution is some kind of healthcare intervention. The intervention could be a product such as a drug or medical device. Or it could be an entire program such as a lipid clinic.

But how do we really understand what the market is looking for?

We can start with our own experience and some secondary research (i.e., literature reviews). Ideally, we also pursue market research to understand the nuances of what the market wants. In market research, we identify our target market and ask them about their problems. When we listen, we pick up on nuances that help us address exactly what our potential customers are looking for. For example, we might learn through market research that patients in our target market find existing treatments difficult to administer. With this kind of insight, we now know that offering a treatment with less administration burden (e.g., fewer injections per day or week) has value.

The good news is that market research doesn’t have to be complex. Once we identify individuals or groups in our proposed target market, we do the following:

- Develop a list of questions for our target audience (i.e., an interview guide)

- Schedule the one-on-one interviews, focus groups, and/or surveys

- Analyze and synthesize the findings

In addition to market research, reimbursement in healthcare provides insights for what kind(s) of evidence to generate.

In healthcare, there are two primary ways products and services are paid for: 1) fee-for-service (FFS) and 2) alternative payment models (APMs).

The FFS system is built on established billing codes that represent specific products and services administered in the delivery of healthcare (e.g., Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes for medical services, National Drug Code [NDC] codes for medications).

The APMs provide many emerging opportunities for evidence generation in healthcare. APMs offered by payers and CMS often incentivize quality by paying bonuses based on outcomes. Thus, any new healthcare intervention that helps providers meet these outcomes offers value. For example, consider an APM that incentivizes lowering the risk of heart disease in the form of lower blood pressure (BP). When we have a new medication demonstrating superior BP reductions from current standard of care, we have something of value for provider groups. We can prove to providers our new medication will help them meet or exceed quality metrics tied to bonus payments.

Once we understand what our market is looking for and what it pays for, we can start thinking about how to generate the evidence we’ll need to prove value that meets their needs or solves their problems.

STEP #2: Generate evidence using established scientific methods and tools

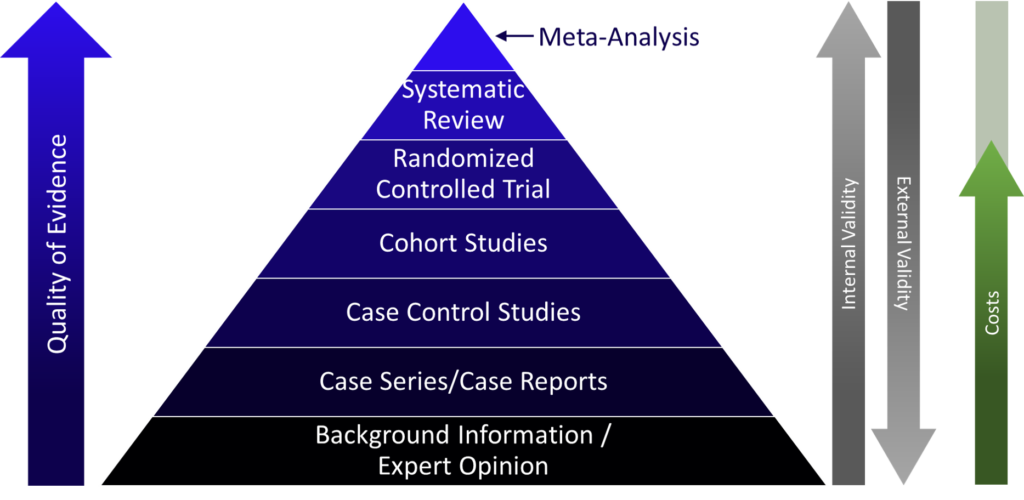

There are many methods from which to choose to generate evidence in healthcare. First, consider the classic “Evidence Pyramid” that highlights the different types of studies available:

So how do we choose?

There are a handful of key drivers and considerations for each.

The gold standard is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). Why? In short, the RCT is the gold standard because of its ability to answer the cause-and-effect question. In any comparative study, we need to control for all possible confounders so we can isolate our findings to the single cause-effect relationship we are hoping to prove. The magic of randomization is that it controls for the 1000’s of potential confounders we don’t know about. In other forms of research (e.g., cohort studies), we can still control for potential confounders, but only those that we know about. RCTs allow us to control for those we know about and those we don’t. The biggest downside of RCTs is that they can be expensive, both in terms of time and dollars.

A meta-analysis generally combines the evidence from multiple RCTs to create a higher level of confidence in the group of study findings. Thus, they are much cheaper, but they are built upon the investments in multiple prior RCTs. Systematic reviews are similar except they tend to include all study types rather than only RCTs.

Another key characteristic of RCTs is their high level of internal validity. High internal validity simply means there is high confidence in the study findings when we repeat it in the same type of population. This last part is key – in the same type of population. Most clinical trials are highly selective about which subjects they include. Many subjects are excluded because they may confound the study results. While this approach gives us confidence in the cause-effect relationship we are examining, it tells us very little about how effective the intervention will be in the real world. In real-world settings, the intervention will likely be utilized in patients that did not meet inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study, besides their diagnosis.

The limited external validity of RCTs highlights the complementary role for studies that generate real-world evidence (RWE). RWE approaches tend to have high external validity since they are generated in real-world populations that are not as “scrubbed” as those from clinical trials. Study approaches that are commonly used to generate real-world evidence are observational studies that include study designs like cohort studies, case control studies, case series/case reports, and expert opinion studies. The findings from these kinds of studies have much higher external validity than RCTs because they use observational data from real-world settings.

STEP #3: Position the evidence against existing interventions

Another key consideration when building data to support value is how we will position our evidence. Let’s face it, healthcare interventions do not exist in a vacuum. And it’s a mistake to ignore the competitive landscape. Doing so will drastically limit our progress, cost us time and money, and prevent us from reaching our goals.

“Positioning” is a marketing concept championed by authors Al Ries and Jack Trout in the book of the same name.4 Ries A, Trout J. Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2001 Their work notes the most effective market messaging in today’s overcrowded and overcommunicated society finds a home in their customers’ minds.

If we are the first of our kind, we have an advantage. However, we still need to position against existing alternatives. When we join an already established market, be it just one or many alternatives, we need to own a unique space. It is a waste of time, effort, and money to try to take over an existing position another product or service already owns. The wise approach is to position our solution somewhere new and own it instead. In healthcare, we can use the data we generate to prove we own our unique position.

For example, consider two new drugs for a generic metastatic cancer. Both are effective in clinical trials, but Drug A has stronger efficacy results than Drug B. Drug B also has data in patients with active brain metastases. These two products will quickly take their positions in the minds of prescribers. Drug A will be positioned as the most effective option in metastatic cancer. Drug B will be positioned as an effective option in patients with metastatic cancer that also have brain metastases. While Drug A may want to grab all patients – with and without brain metastases – it is likely a better investment to build on its potency position rather than invest in trying to dethrone Drug B for the brain metastases sub-population.

Another approach is to recognize the position our competition already owns and then play off of that. For example, let’s say we are trying to find a position for a new immuno-oncology (IO) agent for cancer patients. Existing treatments are largely chemotherapy. We know that chemotherapy is already positioned in the minds of patients as quite toxic – causing hair loss, nausea and vomiting, blood disorders, etc. The positioning for our new IO agent can be as simple as “a new, non-chemo treatment option.”

Once we have the evidence and a clear position for the market, we now want to promote. That leads us to our last core skill in the ABCs of value… Communicate Value.

C is for Communicate… Learn to Communicate Value

The third key skill in doing value on purpose is to know how to communicate value.

We cannot drive the results we are looking for in healthcare without being able to communicate our value well.

The Value Vitals 3-step approach for communicating value is:

- Focus on what the market wants and the ideal position in their minds

- Develop a marketing story highlighting the problem and solution

- Package the story in marketing materials and deliver them where your audience lives already

STEP #1: Focus on what the market wants and the ideal position in their minds

The first step in communicating value well is to revisit something we introduced when we were building value – know what our audience cares about.

Back then, we considered their wants in order to direct what evidence we should generate. This time, we consider what they care about so we can speak directly to them in terms that resonate, capture their attention, and motivate them to engage with our solution.

In addition, we want to consider the ideal position to take in their minds. In our examples above, Drug A positioned well as a highly potent new treatment for metastatic cancer. Drug B positioned well as ideal for those patients with metastatic cancer with active brain metastases.

When taken together, the market desire (e.g., better treatments for patients with metastatic cancer) PLUS our marketing position (i.e., high potency and/or activity in brain mets) informs effective market messaging. Drug A can speak to the market desire in terms of “unprecedented efficacy” in late-line prostate cancer. Drug B can speak to the market desire in terms of “efficacy in patients with brain mets.” Each finds a solid, defensible space in the minds of providers, patients, and payers.

STEP #2: Develop a marketing story highlighting the problem and solution

Of course, soundbites are only part of the big picture for any given healthcare intervention. We need to be able to package all the value we offer into something consumable. And that’s where story-telling comes in.

Story-telling is perhaps the most persuasive form of marketing.

People love stories and they remember them. They tap into the emotion within each individual. In fact, story and emotion are major ingredients in the highly effective TED talk format.

So we know stories are effective for communicating our value, but they don’t just happen. They take a bit of effort to create. That being said, there is a dependable framework we can follow to develop stories that communicate our scientific value:5 Clare J. Storytelling: The Presenter’s Secret Weapon. New Generation Publishing. 2019

- Capture attention with an opener (e.g., a surprising statistic, quote, image, word picture, audience poll, call to future state)

- Widen the subject introduced in the opener

- Deliver the story outline (3 items is ideal)

- Provide details for Item 1

- Provide details for Item 2

- Provide details for Item 3

- Summarize the discussion

- Present a call-to-action (CTA)

- Close the story, ideally with connection to the opener

Let’s consider our story framework with a hypothetical example for Drug O, a new treatment for a type of advanced cancer (Cancer C).

- Capture attention with an opener (e.g., a surprising statistic, quote, image, word picture, audience poll, call to future state)

Every 10 minutes, another mother, wife, and daughter dies from cancer C in the United States (52,560 per year).

- Widen the subject introduced in the opener

Oncologists who fight metastatic Cancer C have limited options once these patients fail two lines of therapy. Currently, there is no standard of care for 3rd-line metastatic Cancer C. Patients are forced to recycle prior therapies with limited efficacy (e.g., overall response rates [ORR] = 35%, median progression-free survival [mPFS] = 3.6 months, and median overall survival [mOS] = 6.2 months), enroll in a clinical trial if able, or give up.

But imagine if we had a new treatment option. One with unprecedented efficacy that more than doubles current treatment outcomes, even in patients who have been heavily pretreated.

- Deliver the story outline (3 items is ideal)

Today we will share data for a new medication that may become the first ever standard of care in 3rd-line metastatic Cancer C. We will discuss the mechanism of action, the unprecedented efficacy of Drug O, and the adverse event profile associated with Drug O.

- Provide details for Item 1 (Mechanism of Action)

Drug A works by targeting Cancer C cells. It targets proteins on the surfaces of Cancer C cells and then kills those cells. It is designed only to attack Cancer C cells while leaving normal cells alone.

- Provide details for Item 2 (Efficacy of Drug O)

In clinical trials in metastatic Cancer C patients, Drug O was associated with a 69% ORR, mPFS of 15.9 months, and mOS of 24.7 months. The study population was heavily pretreated with a median of 5 lines of prior therapy.

- Provide details for Item 3 (Safety of Drug O)

In clinical trials, Drug O was associated with high rates of gastrointestinal and hematologic adverse events. Primary events were nausea (62%), anemia (12%), and neutropenia (17%). These types of adverse events are common with many cancer drugs and are considered to be manageable.

- Summarize the discussion

The burden of metastatic Cancer C is substantial, killing over 52,000 people per year in the United States. Currently, these patients have no accepted standard of care after failing two lines of therapy and their outcomes are poor. A new medication, Drug O, has shown promising results in clinical trials with RR of 69%, mPFS of 15.9 months, and mOS of 24.7 months. These unprecedented efficacy results were achieved despite the population being heavily pretreated (median lines of prior therapy = 5). Adverse events favored gastrointestinal and hematologic events and were considered to be manageable.

- Present a call-to-action (CTA)

Consider Drug O for the appropriate patient who has metastatic Cancer C for unprecedented efficacy regardless of the number of lines of prior therapy.

- Close the story, ideally with connection to the opener

With unprecedented efficacy, Drug O has the potential to provide a SOC for the first time ever in patients who fail existing treatment options in 1st and 2nd-line or beyond. Drug O has the potential to limit the number of mothers, wives, and daughters that die prematurely from metastatic Cancer C in the United States.

———-

Hopefully, we can appreciate how packaging our value and our data for Drug A in this story format accomplishes the following:

- Grabs attention

- Emphasizes existing unmet needs

- Educates on a new solution that can improve care dramatically

- Guides the listener/reader to exactly what we want them to do next

- Leaves a memorable impression

STEP #3: Package your story in marketing materials and deliver them where your potential customers live

Now that we have identified what the market cares about (i.e., novel products with efficacy in late-line disease), aligned it with our winning position (unprecedented efficacy late-line Cancer C), and packaged it in a story (even heavily pre-treated patients responded to treatment), we need to put it in the right package to be seen and delivered where we want it.

First, we package our messaging with the story and supportive data in whatever formats make the most sense. We will want to develop a slide deck that tells the story along with supportive data for one-on-one presentations. We will also want to create print ads that highlight the key pieces of the story (and supportive data) for various audiences. We may even consider other media like radio and television advertisements.

Second, we look to deliver our messaging to our target audiences. In order to do this well, we need to know who they are and where to find them. In healthcare, we are often targeting providers, prescribers, or patients. We will customize our messaging for each audience depending on what is most important to them. For example, patients might care most about the safety profile of the drug while providers care about the strength of efficacy data.

Third, we want to be sure to include a call-to-action (CTA). We ask ourselves what is the singular action we want our audience to take when they see, read, and/or hear our messaging? We make sure to include that request explicitly. For example, for a payer, we want to ask them to add our Drug O to formulary to make it available for their beneficiaries. For a patient, we want to ask them to ask their doctor about Drug O. And for providers, we want to ask them directly to consider Drug O for their appropriate metastatic Cancer C patients.

For media market beyond one-on-one meetings, it is best to know where our audiences already hang out. Our key target markets in healthcare – providers, patients, and payers – get their information from very different sources. For example, if we want to reach providers, we’ll look for advertising space in primary medical journals they read (e.g., JAMA, NEJM, etc.). If we are trying to reach patients, we can consider print ads in popular consumer magazines (e.g., Good Housekeeping, Time, Women’s Health). When trying to reach payers, we consider scientific journals that are frequented by them (e.g., AJMC, Health Affairs).

Closing: The Secret Skill Set that Helps Everyone Win in Healthcare

We hope this article has been enlightening about the potential of the ABCs of Value in healthcare.

With this skillset, anyone can start improving the health and well-being of individuals, populations, and society as a whole. We believe that when these skills are applied, they help everyone win in healthcare.

In this article, we discovered how assessing value in healthcare empowers us to decide which interventions are worth it and what healthcare products or services to develop. We identified multiple ways to build value for new or existing healthcare products and services. And we explored the most effective ways to communicate the value of healthcare products and services.

If you have any questions or comments, or if you’d like to partner with us in your own mission, please do not hesitate to contact us directly at admin@valuevitals.com.

References

| 1 | CMS. Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data. Accessed January 2021 |

|---|---|

| 2 | IBM Micromedex Red Book. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/products/micromedex-red-book. Accessed January 2021 |

| 3 | Health Measures. Intro to PROMIS®. Available at: https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis. Accessed January 2021 |

| 4 | Ries A, Trout J. Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2001 |

| 5 | Clare J. Storytelling: The Presenter’s Secret Weapon. New Generation Publishing. 2019 |