Traditional fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement programs are being rapidly replaced with alternative payment models (APMs).

In the FFS model, private and public payers reimburse healthcare providers and institutions based on their consumption of healthcare products and services.

As a result, FFS tends to incentivize providers financially to treat patients in a way that consumes healthcare resources.

But those who shoulder the majority of the healthcare bill in the United States – public and private payers – would like to eliminate such incentives.

Specifically, payers are looking for ways to incentivize less consumption of healthcare resources while simultaneously increasing quality of care and improving health outcomes.

To accomplish these goals, they are developing alternative payment models or APMs.

Ultimately, alternative payment models are being employed by payers in their efforts to move from volume to value. That is, paying healthcare providers and institutions based on the value of the care they deliver instead of the volume of care.

As of 2016, the largest payer in the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has dozens of alternative payment model programs in place. They call them “Innovation Models.” Furthermore, CMS has set targets to spend 30% of their total reimbursements by 2016 under alternative payment models and 50% by 2018.

As you probably know, CMS tends to set the trends for other payers. As such, private commercial insurers are already adopting and adapting CMS’ alternative payment models in their own contracts with providers and institutions.

Purpose of This Series

Given the pace with which alternative payment models are being implemented, healthcare providers and executives are under increasing pressure to understand the rapidly changing reimbursement environment. Those that do will help their organizations thrive in the new healthcare economy. Those that do not adapt will likely be consumed.

At the same time, there is a very practical side to the effort for providers to operationalize alternative payment models in their local environments.

Many healthcare providers and executives do not have much time to get sophisticated training about alternative payment models. They do not have much time to plan ahead for the necessary staffing, training, and IT infrastructure investments that may be necessary to succeed in their practice. After all, there is plenty of work to do just managing the FFS business they are already successfully running day in and day out.

That’s why I am writing this simple 6-part series to introduce basics of alternative payment models.

This series of articles will rapidly get healthcare providers and executives up to speed with what you need to know to plan for success with alternative payment models.

In this first article, I’ll give a brief overview of 5 of the most common types of alternative payment models. In subsequent articles, I will go into more depth about what you need to know… and do… to succeed with each.

Defining Alternative Payment Models (APMs)

Alternative payment models take on many forms.

As such, they may be best understood by what they are NOT – fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursements.

Medical practices and institutions have become top-notch experts with FFS reimbursement systems. Health plans have forced providers hone their skills through complicated claim approval and denial schemes (i.e., claims codes and modifiers).

While the FFS can be seen as a simple model to implement, its major drawback continues to be how it invites what is known as “moral hazard” in economic terms.1 [1. Keast SL, Skrepnek G, Nesser N. State Medicaid programs bring managed care tenets to Fee for Service. JMCP. 2016;22(2):145-157] In health economics terms, moral hazard is the “lack of incentive to guard against risk where one is protected from its consequences.“

Put simply, the providers consuming more services actually receive greater benefit in the form of more payments.

Without incentives to check the utilization of medical products and services, providers drive higher demand for things like additional diagnostic test or interventions. They also shift demand towards relatively more profitable diagnostics or interventions.

The profit potential for each patient is impacted by the number of products and services consumed by that patient as well as the price per unit of those products and services. Under FFS, the provider bills for each component.

Even while providers and institutions are focused on “appropriate” care, they can consciously or unconsciously shift towards a higher per-patient revenue care. For example, it has been shown that institutions look to shift patients towards relatively higher-paying DRG codes when they submit claims.2 [2. Dafny LS. How do hospitals respond to price changes. Available at: https://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/faculty/dranove/htm/dranove/coursepages/Mgmt%20469/Dafny_Hospitals.pdf. Accessed 3/2016]

These dynamics are all quite logical. After all, medical practices and institutions are businesses. Like any business motivated to remain whole, providers and institutions are required to find ways to run in the black. It is the only way to keep the doors open and serve more patients.

But those paying the majority of the healthcare bills – CMS and health insurers – are looking for ways to overcome FFS volume-based financial incentives. At the same time, they are looking to shift some of the risk towards the providers in the form of value-based financial incentives.

Some of the most common alternative payment models they are employing can be broadly classified into the following 5 types:

- Pay-for-Reporting (PFR)

- Pay-for-Performance (PFP)

- Bundled Reimbursements

- Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

- Patient Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs)

Below is a short introduction to each of these alternative payment models.

Pay-for-Reporting (PFR)

We’ll start with pay-for-reporting (PFR).

Under pay-for-reporting alternative payment models, providers and institutions get paid for reporting.

Specifically, for reporting valuable data to the payer. The data reported can get complicated, but generally they are related to specific quality metrics.

These quality metrics are developed, sponsored, and published by healthcare organizations that range from government organizations (e.g., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS]; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ]) to independent policy organizations (e.g., National Committee for Quality Assurance [NCQA]) to provider organizations (e.g., American Society of Clinical Oncology [ASCO]).

One of the most widely implemented pay-for-performance programs in the United States is CMS’ Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) program.

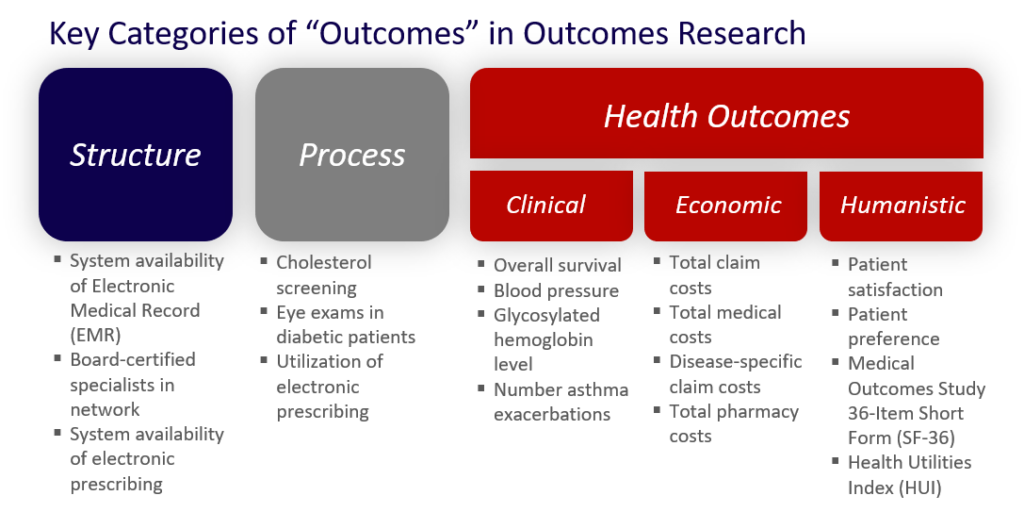

PQRS is a set of nearly 300 (and growing) quality metrics. These metrics span structure, process, and outcomes metrics. This illustration gives a few examples of each.

(Click HERE for more info about the differences in types of outcomes metrics.)

The program works like this for participating providers and institutions:

- Interested “Eligible Providers” (EPs) or Group Practices enroll in the program

- Enrolled EPs and Group Practices collect and report required data back to CMS annually

- Enrolled EPs and Group Practices are rewarded (prior to 2015) or penalized (as of 2015 reporting year) x% of their pay from CMS on all eligible claims

Find out more PQRS in our detailed article HERE.

Importantly, under PFR there is no real transfer of risk for what the patient costs the system shifted to the provider side.

| Technical Needs | Incentives | Risk Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal – ability to pull claims into a spreadsheet, calculate a numerator and a denominator | Financial opportunity / penalty for the practice | 100% payer (e.g., CMS) |

Pay-For-Performance (PFP)

The concept of pay-for-performance (PFP) takes pay-for-reporting (PFR) one step further.

Under pay-for-performance, providers and institutions are still reporting their data…

…but now they are accountable to the performance as shown in the data.

The same kinds of metrics used in pay-for-reporting are used in building pay-for-performance programs. Providers and institutions are financially incentivized by reward or penalty to achieve the targets set in the metrics.

So instead of being paid (or penalized) simply for reporting average HgbA1c levels for their diabetic patients, the provider group or institution is paid (or penalized) for the average HgbA1c level below (or above) 8% on eligible claims.

We’ve already seen how CMS uses the PQRS quality metrics to drive reporting from providers and institutions on outcomes of the care they provide.

But there are hundreds of quality metrics and sets of quality metrics. Private payers build their own pay-for-performance programs with these quality metrics to drive quality healthcare.

One of the most widely applied commercial quality metric sets in pay-for-performance programs is produced by NCQA – a leader in health plan accreditation.

NCQA has developed the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) – a set of over 80 metrics across 5 domains of care. Over 90% of US health plans use the HEDIS metrics to measure performance on aspects of care and service.3 [3. NCQA. HEDIS® & Performance Measurement. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement.aspx. Accessed March 2016]

As a side note, the HEDIS metrics provide a great example of how savvy providers and institutions can develop value propositions for their payer customers. Solid payer value propositions can help them acquire or improve contracts with payers. You can read all about it in my FREE eBook titled – “How to Motivate Payers to Increase Your Reimbursements.”

In short, payers are motivated to obtain and maintain NCQA accreditation. That’s because accreditation helps them sell better/more to their employer customers. Part of achieving accreditation is tied to HEDIS scores from the payer’s provider networks. Thus, any provider or institution that routinely meets or exceeds these metrics will have innate value to the payer. The provider just needs to have the data to document and prove it.

Of note, many pay-for-performance programs start by offering positive incentives like bonus payments to providers. Over time, they tend to shift towards negative incentives in the form of financial penalties for providers.

CMS is notorious with this approach. Consider the Medicare STAR program of rating health plans. The Medicare STAR program started in 2005 by rewarding private administrator health plans for their Part D benefit with bonuses that were high performers as scored by the STAR ratings scale. Plans that earn at least four stars receive a 5% boost to their monthly per-member payments from Medicare, while those with lower scores receive nothing extra. Since 2014, Medicare reserves the right to terminate contracts with plans that do not achieve at least a 3-star rating over 3 years.

Beyond the HEDIS and STAR metrics, there are hundreds of different metrics with dozens of sponsors/developers. It can be very difficult, if not impossible, to know them all.

Thankfully, there is a very useful resource provided by yet another organization that is a major player in the quality metric space – the National Quality Forum (NQF). NQF is a not-for-profit organization that not only develops their own quality metrics, but also consolidates and endorses quality metrics developed by different organizations. You can find a searchable database of metrics provided by NQF HERE.

Additionally, the administrative burden on providers and institutions can be high with pay-for-performance programs.

With so many metrics and so many different payers building different incentive programs, it can be challenging to keep them all straight in a way that optimizes reimbursements.

| Technical Needs | Incentives | Risk Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal – collect, analyze, and report data | Financial opportunity / penalty for the providers based on quality of care as assessed by quality metrics included in the program | 80% payer |

| Complicated by number of different programs required by multiple payers (i.e., public and private) | 20% provider (taking on risk as responsible for outcomes of care, not just clinical activities performed on behalf of the patient |

Bundled Reimbursements

“Episode-based” or “bundled” reimbursements are lump-sum payments for groupings of medical products or services used to treat patients.

Bundled payments have been utilized in healthcare reimbursement for some time now. We are all familiar with the Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) and Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC) systems.

Essentially, bundling programs simplify reimbursement by assigning a single dollar reimbursement amount to a group of clinical, demographic, and disease characteristics that are expected to relate to a relatively predictable and similar level of healthcare resource utilization – and their associated costs.

The DRG system brought simplicity in billing for institutions. Hospital stays that generally include dozens if not hundreds of individual healthcare products and services could be reduced to a single claim code for reimbursement.

The DRG system also brought predictability for payers of their expenses. For example, consider a patient hospitalized for bypass surgery. These patients may be hospitalized anywhere from 3 days to upwards of 14 days. Prior to DRGs, payers were left wondering if their bill would be $15,000 or $75,000 for their bypass beneficiary. With DRGs, the payer knows they will be responsible for a flat “bundled” fee of $25,000, regardless of how long the patient spent in the hospital.

Bundled payments also tend to shift more risk towards the providers. After all, the hospital loses money when 1 patient spends 10 days in one of their hospital beds instead of turning over 2 patients in that bed within the same time period. With our bypass example, the hospital charges 1 DRG worth $25,000 for the patient spending 10 days and 2 DRGs worth $25,000 each ($50,000 total) for 2 patients spending 5 days each in that bed.

While DRGs and APCs have been around for a while, payers are looking for even more ways to bundle healthcare products and services delivered by healthcare providers and institutions.

Take oncology, for example, which is a notoriously expensive therapeutic area.

In oncology, CMS has announced a new program called the Oncology Care Model (OCM) program. This 5-year pilot starting in 2016 includes a bundled payment of $160/patient to manage care coordination. CMS leaves it up to the oncology practices to determine how to spend this money in order to achieve the objective of generating savings for their Medicare population.

As you can see, bundled payments transfer risk in a tangible way to the providers. Suddenly, providers have a set budget with which to manage and produce patient outcomes in a way that is financially beneficial to their business.

| Technical Needs | Incentives | Risk Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate to Significant – submitting accepted codes for reimbursement is easy but managing healthcare resource utilization for patients’ medical care to remain profitable may not be | Providers incentivized to drive lowest consumption of healthcare resource utilization per patient | Payer – 70% (predictability but providers still motivated to churn through payments) |

| Providers motivated to drive patient turnover to be able to bill for relatively more outcomes expected by specific sets of program metrics | Provider – 30% (taking on risk when responsible for outcomes and associated costs of care, not just the care activities they perform) |

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) were born out of the landscape healthcare reform bill passed by President Obama in 2010 – the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

ACOs take many forms, but they share a couple of common characteristics:

- Healthcare provider groups and/or institutions that join together voluntarily to provide coordinated care

- Attributable patients – patients for whom the ACO is held accountable for clinical and economic outcomes

- Shared risk for the clinical and economic outcomes of attributable patients

CMS offers ACOs bonus payments paid out of any savings they could produce for Medicare over a given year.

There are two primary ACO programs offered by CMS:

- Pioneer program

- Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP)

The Pioneer program was piloted from 2012 through 2015 before a larger roll-out.

In the pilot, 32 organizations participated by special application and qualification by CMS.

These organizations tended to be sophisticated integrated delivery networks (IDNs) with much of the infrastructure already in place predicted to drive success with such a model. In fact, many of them believed they already had decades of experience operating like ACOs. As such, the Pioneer program represented an opportunity for a new revenue stream with minimal additional operational and technical investments. In fact, the Pioneer program offered the highest level of potential reward for any of CMS’ ACO programs. In addition, 2 years of success in the program qualified an ACO for a population-based payment model – a per-beneficiary per month payment amount.

Despite their anticipated advantages, 9 groups dropped out after the first year and 3 more by 2014. Only 20 made it through all 3 years of the pilot. Two of the biggest reasons cited lack of success were the reporting methodologies required by CMS and patient attribution issues.

Following the pilot, the program was opened to a wider audience for participation. At this time, only 9 organizations are participating in Pioneer.

In contrast, there are hundreds of ACOs participating in the MSSP program which was opened to all organizations qualified as ACOs. Many of the former Pioneer ACOs have joined MSSP instead.

Under MSSP, Medicare offers a percentage of any shared savings from Medicare’s prior spend with that ACO group as a bonus to the providers.

MSSP offers a one-sided track and a two-sided track. For both tracks, a benchmark level of spend is established. Then, the one-sided track offers a bonus to the ACO group when savings are achieved but without penalty when spending is over the benchmark. These participants are eligible to receive up to 50% of the shared savings with Medicare.

The two-sided track offers a higher bonus to the ACO group when savings are achieved and a penalty when spending is over the benchmark. These participants are eligible to receive up to 60% of the shared savings with Medicare.

Similar to the pay-for-reporting and pay-for-performance models described above, private commercial payers have started to model CMS’ ACO programs.

The ACO model shifts even more risk and accountability from the payer to the provider side than the above models. The payer still carries the majority of risk at this time since the payments generally represent opportunities for additional provider revenue rather than penalties imposed by payers when targets are not met. It would not be surprising, however, if over time the current positive incentives shift more towards negative incentives.

| Technical Needs | Incentives | Risk Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Significant – collect, analyze, and report data across sites of care for attributable patients | Providers incentivized to drive costs lower by reducing waste and driving better patient outcomes per a set of 33 specific metrics | 60% payer |

| 40% provider (taking on substantial risk as responsible for clinical and financial outcomes of care, not just clinical activities performed on behalf of the patient) |

Patient Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs)

The patient centered medical home (PCMH) is a team-based model with the patient in the center and an “on-call” provider and care team surrounding them.

The central provider and care team function as a quarterback to deliver and/or route the patient to appropriate services at the right time, in the right place, and in a fully coordinated manner.

Management of the health needs of the PCMH team spans primary and secondary care, preventive care, acute care, chronic care, and end-of-life care.

In short, PCMH transitions the typical episodic care model into one that involves continuously accessible communication and care for patients.

There are 2 critical components to the PCMH model:

- Communication

- Sharing information

Although the primary care physicians who organize themselves within a PCMH model can reap substantial rewards from payers, there are investments the typical practice has to make to qualify as a PCMH. These include:

- Staffing

- IT infrastructure

Private and public payers are offering monetary benefits to primary care practices that organize and document PCMH services.4 [4. Weiss GG. PCMH: A closer look at a trend changing healthcare delivery. Available … Continue reading

Why?

Because they are proving to improve quality while reducing the costs of care. They help patients avoid unnecessary trips to the hospital, avoid medication errors, avoid duplicate tests, and synchronize referrals.

| Technical Needs | Incentives | Risk Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate to Significant – communication and information sharing infrastructure are critical for success | Financial benefits from public and private payers | Payer – 60% (predictability but providers still motivated to churn through payments) |

| Significant staff hiring and/or training for clinical and clerical tasks | More time to see patient | Provider – 40% (taking on risk when responsible for outcomes and associated costs of care, not just the care activities they perform) |

| Enhanced quality of care | ||

| Reduced waste in healthcare |

Wrap-Up

In this introductory article, we’ve reviewed the basics about 5 of the most common alternative payment models emerging in the US healthcare reimbursement environment.

We’ve seen how they are all the same in that they are looking to move healthcare reimbursement away from payment based solely on healthcare resource consumption (i.e., FFS). The public and private payers developing alternative payment models are looking to move from reimbursing on volume to value.

Alternative payment models are designed to do just that… reimburse based on outcomes associated with the consumption of healthcare products and services.

Five of the most common types of alternative payment model programs we presented here include:

- Pay-for-Reporting (PFR)

- Pay-for-Performance (PFP)

- Bundled Reimbursements

- Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

- Patient Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs)

I go into greater detail in the remaining articles in this series, “Alternative Payment Models Made Simple.”

Read the next article in this series, “Alternative Payment Models Made Simple – Pay-For-Reporting (Part 2 of 6)” by clicking HERE.

In the meantime, be sure to sign up for our newsletter so you’ll get our articles delivered automatically to you immediately when they’re published.

References:

References

| 1 | [1. Keast SL, Skrepnek G, Nesser N. State Medicaid programs bring managed care tenets to Fee for Service. JMCP. 2016;22(2):145-157] |

|---|---|

| 2 | [2. Dafny LS. How do hospitals respond to price changes. Available at: https://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/faculty/dranove/htm/dranove/coursepages/Mgmt%20469/Dafny_Hospitals.pdf. Accessed 3/2016] |

| 3 | [3. NCQA. HEDIS® & Performance Measurement. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement.aspx. Accessed March 2016] |

| 4 | [4. Weiss GG. PCMH: A closer look at a trend changing healthcare delivery. Available at: http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/content/tags/american-academy-family-physicians/pcmh-closer-look-trend-changing-he. Accessed March 2016] |