In this article, we will cover pay-for-reporting (PFR) in detail.

This article is Part 2 of our 6-part series simplifying alternative payment models in healthcare.

If you missed Part 1, or want to jump around to other parts of the series, here are the links:

- Alternative Payment Models Made Simple – Overview (Part 1 of 6)

- Alternative Payment Models Made Simple – Pay for Reporting (PFR) (Part 2 of 6) (THIS ARTICLE :))

- Alternative Payment Models Made Simple – Pay for Performance (PFP) Part 3 of 6)

- Alternative Payment Models Made Simple – Bundled Reimbursements (Part 4 of 6)

- Alternative Payment Models Made Simple – Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) (Part 5 of 6)

- Alternative Payment Models Made Simple – Patient Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) (Part 6 of 6)

Introduction to Pay-for-Reporting (PFR)

As we mentioned in our overview article for this series, pay-for-reporting is just like it sounds.

That is, the provider or institution is reimbursed (or penalized) for reporting information to the payer.

As such, pay-for-reporting alternative payment model programs have 3 consistent components:

- A payer

- A set of target metrics

- A provider / institution

The payer develops a pay-for-reporting program that consists of criteria the provider or institution must meet in order to qualify for the reporting-based reimbursement.

The Payer

As a business, the payer collects health insurance premiums from their member population. In exchange, they become responsible for paying for the majority of the health bills that accrue from those beneficiaries.

As such, the payer is highly motivated to insure a relatively healthy population.

But consider how little influence the payer has on the actual health status of each beneficiary. Instead, they must rely on their provider and institution networks to provide a level of quality care that results in a “less sick” or “well-managed” population.

On the surface, payers are motivated to have completely healthy members that never use health services. In fact, plans refusing to cover very sick patients and canceling those that racked up high healthcare bills were common practices before health reform in 2010.

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) built in provisions that incentivize health plans to insure relatively sicker populations. The bill also mandated health coverage ostensibly providing more cash flow for health plans from the 80% of healthy people to cover the 20% of their sick beneficiaries.

Under both scenarios – enrolling relatively healthy populations or sick populations – the payer is always motivated to minimize what their members actually consume (and spend) in terms of healthcare resources. Thus, payers are motivated to manage even their sickest beneficiaries to a healthier state so as to consume fewer healthcare resources. When they receive higher reimbursements for higher risk-adjusted members and spend less on them throughout their enrollment year, they keep the difference.

Since the payers generally do not touch the patient, they rely on the providers to drive optimal patient outcomes that minimize healthcare resource consumption… and the costs associated with them.

As such, the payer wants to incentivize those who see their members (the providers and institutions) to provide care that achieves a healthy, well-managed patient population.

But how can they do that?

One way is to try to hold providers accountable to delivering “quality care.” But “quality care” has to be defined.

And that’s where the next piece comes in – the metrics of quality care.

Target Metrics

Target metrics in pay-for-reporting programs are generally comprised of outcomes metrics.

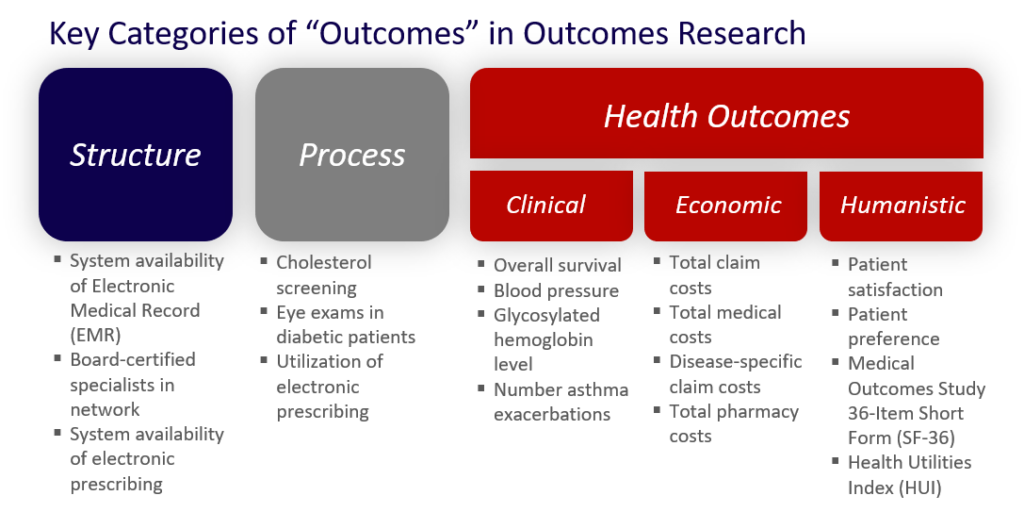

Importantly, one outcomes metric is not the same as another outcomes metric. In fact, outcomes metrics can be broadly classified into those that are structure, process, and health outcomes metrics.

Structure and process metrics tend to be easier to administer and control. As such, they are more popular. However, most of what we think if in terms of quality of healthcare falls in the health outcomes bucket.

(You can read more about the different types of outcomes metrics HERE.)

Many types of organizations have developed sets of quality metrics comprised of these outcomes metrics.

Then these metrics are employed in pay-for-reporting programs.

Organizations developing quality metrics range from government organizations (e.g., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality [AHRQ]), academic institutions (e.g., University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus), provider organizations (e.g., American College of Cardiology, American Society of Clinical Oncology), and private organizations like (National Committee for Quality Assurance [NCQA], California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative).

These organizations use their clinical and healthcare expertise to develop outcomes metrics that logically relate to quality healthcare.

There are literally dozens of sponsors who develop hundreds of metrics. Many times, they include metrics developed in other sets.

Some of the most frequently utilized by payers in the US include the following:

- Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) sponsored by CMS

- Healthcare Effectiveness Data & Information Set (HEDIS) sponsored by NCQA

PQRS

CMS launched the PQRS pay-for-reporting program, formerly known as the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) program, in 2007.

The program has a few basic components.

First, participants must officially qualify as an eligible physician, practitioner, or therapist.

Then, they must decide whether they will participate in PQRS as an individual or as a group practice. Essentially, will each individual be accountable to the reporting on their patients or will the group aggregate the data across all providers. Of note, PQRS only applies to Medicare Part B claims.

Next, the provider or group will choose a reporting mechanism.

As you can imagine, reporting can get complicated quickly. Data for a group of patients needs to be aggregated and analyzed. Then it needs to fit nicely into a report with highly prescribed specifications from CMS.

Reporting can be broadly classified into claims reporting, registry reporting, certified electronic health record technology (CEHRT) reporting, and qualified clinical data registry (QCDR) reporting.

Claims reporting involves adding Quality Data Codes (QDCs) to eligible Medicare Part B claims when submitting them to CMS. Eligible claims would be those that are relevant based upon the provider’s chosen set of metrics. There are almost 300 metrics in the PQRS at the time of this writing. Participating providers are required to select a batch of 9 metrics covering at least 3 different domains.

Registry reporting involved entering into a contracted agreement with a qualified PQRS registry. These companies provide the service of batching appropriate claims on providers’ behalf in exchange for fees.

CEHRT reporting is an option for practices that have CEHRT in the office or contract with an EHR data submission vendor that is CEHRT.

Finally, QCDR reporting is an option for practices that contract with CMS-approved QCDR entities, such as a registry, certification board, collaborative, etc.) that collects medical and/or clinical data for the purpose of patient and disease tracking in order to improve the quality of care provided to patients.

Payments from CMS for participation in PQRS have shifted from bonuses to penalties as of 2015 (for reporting year 2013).

Specifically, the program started by paying a 0.5% bonus when reporting was deemed “sufficient.”

As of 2015 (for reporting year 2013), CMS now applies a negative payment adjustment of -1.5% for all Medicare claims when reporting is deemed “insufficient.” By 2016 (for reporting year 2014), the penalty increases to -2.0%.

As you can tell, getting up and running and succeeding in the PQRS program is no small task. Optimizing performance and minimizing penalties tied to PQRS requires continual monitoring, staff training, and management.

(NOTE: CMS provides a “How to Get Started” guide HERE for further reference)

HEDIS

Another huge player in the quality metric space is the HEDIS metric set developed by NCQA.

NCQA is a non-profit organization dedicated to driving improvement in quality in the healthcare system. The organization has established an accreditation program for health plans inclusive of over 60 standards in more than 40 areas. Their third-party status has helped it become a sought-after accreditation by health plans.

The HEDIS metrics are a piece of NCQA’s accreditation program. The HEDIS set is comprised of 81 measures across 5 domains of care. The domains include:

- Effectiveness of care

- Access / Availability of care

- Experience of care

- Utilization and risk adjusted utilization

- Relative resource use

While the HEDIS metrics are similar in the outcomes they assess, they differ from the PQRS metrics in that the former hold health plans accountable rather than providers.

We have already discussed how CMS, as a payer, ostensibly reduces costs by motivating providers to achieve PQRS goals.

HEDIS metrics are used widely in the same way with private or commercial payers. In fact, 90% of US health plans utilize the HEDIS metrics to measure performance and quality of the care provided in their network.

By contracting terms with providers and institutions tied to achievement of HEDIS metrics, health plans drive higher quality care ostensibly resulting in cost-effective care that saves money through higher quality care and healthier populations.

You can find a list of the latest metrics HERE.

Read more about the HEDIS program HERE.

Given that CMS and commercial payers are motivated to achieve healthy patients… and that metric sets like PQRS and HEDIS define quality… there is great opportunity for healthcare products and services, and the providers and institutions that deliver to prove the value they deliver to payers. In fact, data demonstrating a provider or institution’s ability to meet HEDIS metrics can be used to build compelling value propositions for payer customers (Read more about this process in my FREE eBook – “How to Motivate Payers to Reimburse You Higher”).

NQF

Before we leave the topic of quality metrics, I want to point you in the direction of a great resource. The National Quality Forum (NQF) is a not-for-profit organization that, among other things, consolidates and endorses quality metrics developed across different organizations.

They provide a great resource that allows one to search both non-endorsed and endorsed quality metrics. At the time of this writing, there are just shy of 1,000 metrics in their searchable database. You can find this database of metrics HERE.

The Provider

Now that we’ve talked about the payer and the metrics, we are ready to address the final component of pay-for-reporting alternative payment models – the provider or institution.

Providers and institutions are at the core of making any pay-for-reporting system successful. Their core function is to provide quality care for patients.

In the past, payers and other stakeholders simply assumed the good intentions of providers to provide the best care for their patients would drive optimal health outcomes, low waste, and appropriate care. As they performed their medical services and prescribed treatments, healthcare resources were consumed. Payers reimbursed providers’ services.

Now, payers are not as trusting. The sheer volume of patients for any given provider and the upward spiral of healthcare costs have forced the system to change and the provider to adapt.

Specifically, the provider has been forced to adapt in two ways:

- Conform to incentives designed to force them into providing quality care

- Document / prove they are providing quality care

Pay-for-performance programs encompass both of these objectives.

Consider how different this environment is for the provider.

| Then | Now |

|---|---|

| Provide quality care | Provide quality care |

| Have benefit of doubt from payers that providing quality care | Need to prove providing quality care |

| Submit claims to payers | Train staff |

| Get paid | Submit claims with additional documentation |

| Collect and analyze data | |

| Develop reports and provide to payer | |

| Get paid |

In short, providers and institutions are required to do a good deal more under pay-for-performance programs. In fact, CMS recognized this fact when they introduced the PQRS program. Any “extra” reimbursements from pay-for-reporting programs will at least in part be necessary to fund providers’ investments in conforming to the program itself.

Providers and institutions have to invest in and create the necessary infrastructure and hire the right personnel to collect, analyze, and report quality data that supports reimbursements.

With the movement towards pay-for-performance (PFP) beyond pay-for-reporting, providers are more at risk of losing money than ever before. The opportunity to gain income is diminishing.

For the payer, while they don’t get the opportunity to keep more of their money with PFR, they DO get a picture of which providers perform best and which fall below the mark. This benchmarking data are quite valuable to them during contracting times. With such information, payers can even decide not to renew contracts with their poorest performers.

Wrap-Up: Pay-for-Reporting

We’ve covered a lot in this article.

We’ve seen how pay-for-reporting programs are built. We’ve also seen just how the key components – the payers, the metrics, and the providers/institutions – are involved and affected.

Payers are motivated to drive quality healthcare that lowers costs. Since they need those who touch their beneficiaries – the providers and institutions -to actually provide that care, payers develop pay-for-reporting alternative payment models to motivate providers to deliver the care.

As such, payers like CMS are creating clinically-driven quality metric sets. Additionally, public and private payers are building their own pay-for-reporting programs from externally created quality metric sets like NCQA’s HEDIS.

All pay-for-reporting programs have one thing in common – they reward (or penalize) providers and institutions for reporting (or not reporting) data tied to pre-specified quality metrics.

In the next article in this series titled “Alternative Payment Models Made Simple,” we’ll discuss how pay-for-reporting can be taken one step further and be transformed into pay-for-performance.

Read the next article in this series, “Alternative Payment Models Made Simple – Pay-for-Performance (Part 3 of 6)” by clicking HERE.

In the meantime, be sure to sign up for our newsletter so you’ll get our articles delivered automatically to you immediately when they’re published.