NOTE: This article is the fifth in a series of 10 articles and is part of our Health Economics 101 course. You can find a course overview and links to all 10 course modules here:

- Health Economics 101: Course Overview

- Module 1: Introduction to Health Economics

- Module 2: Demand and Supply of Health Care

- Module 3: Health as an Economic Good

- Module 4: Health Insurance and Risk Management

- Module 5: Economic Evaluation in Health Care

- Module 6: Health Systems and Health Care Financing

- Module 7: Market Competition and Provider Payment Mechanisms

- Module 8: Equity and Efficiency in Health Care

- Module 9: Health Policy and Regulation

- Module 10: Current Issues and Future Directions in Health Economics

Economic Evaluation in Health Care

Economic evaluation has become a cornerstone of health policy and clinical decision-making, particularly in the context of resource scarcity and rising health expenditures. It provides a structured framework for comparing alternative health interventions in terms of both their costs and outcomes, thereby informing choices that maximize value for money. Economic evaluation encompasses a range of methodologies, including budget impact analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-utility analysis, and cost-benefit analysis. It also involves careful measurement of both costs and health outcomes, making it essential for evidence-based policy formulation and priority setting.

Introduction to Budget Impact Analysis (BIA)

Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) assesses the financial consequences of adopting a new health technology or intervention within a specific budget context, typically over a short- to medium-term horizon (e.g., 1–5 years). Unlike cost-effectiveness analysis, which focuses on efficiency, BIA addresses affordability and financial feasibility.

BIA is crucial for payers, such as government health departments, insurers, or hospital systems, who must assess whether a new intervention can be funded without exceeding budget constraints or displacing other services. BIA models typically estimate:

- The number of eligible patients

- Uptake and market share over time

- Unit costs of the intervention and comparators

- Offsetting cost savings (e.g., from reduced hospitalizations)

BIA is often conducted alongside cost-effectiveness studies to provide a fuller picture of both value and budgetary implications.

Introduction to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA), Cost-Utility Analysis (CUA), and Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA)

Economic evaluation in health care includes several methodological approaches, each with its own strengths and limitations.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)

CEA compares the relative costs and outcomes of two or more interventions, with outcomes typically measured in natural units, such as life-years gained, cases detected, or hospitalizations avoided.

Example: Comparing two treatments for hypertension based on cost per life-year saved.

CEA is particularly useful when outcomes are easily quantifiable but not easily monetized. Results are often expressed as an Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER):

The formula calculates the difference in costs between intervention A and intervention B (i.e., the numerator) and divides that by the difference in the effectiveness measure being compared between interventions A and B (i.e., the denominator).

Cost-Utility Analysis (CUA)

CUA is a subtype of CEA where outcomes are adjusted for quality of life, typically using Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). This allows for comparison across diseases and interventions.

Example: Evaluating cancer treatments in terms of cost per QALY gained.

CUA is favored by national bodies like the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, which often applies a cost-effectiveness threshold (e.g., £20,000–£30,000 per QALY) to guide reimbursement decisions.

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA)

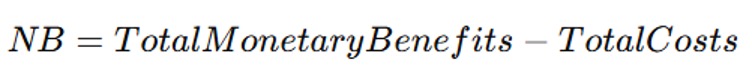

CBA measures both costs and benefits in monetary terms, allowing for direct comparison and broader societal perspective. This allows decision-makers to compare healthcare investments with non-health investments, such as infrastructure or education. The key metric in CBA is the Net Benefit (NB):

Since the benefits have been monetized (i.e., Total Monetary Benefits), the Total Costs can be subtracted to obtain the Net Benefits.

While theoretically appealing, CBA is less commonly used in health care due to the ethical and methodological challenges of assigning monetary values to human life and health.

Measuring Costs in Health Care (Direct, Indirect, and Intangible Costs)

Accurate cost measurement is a critical step in economic evaluation. Costs are typically categorized as follows:

Direct Costs

These include costs directly related to the provision of health services:

- Medical costs: Hospital stays, physician services, diagnostics, medications

- Non-medical costs: Transportation, caregiving, accommodation

Direct costs can be measured from different perspectives:

- Health care provider perspective

- Payer (insurer or government) perspective

- Societal perspective (most comprehensive)

Indirect Costs

These refer to the productivity losses resulting from illness, disability, or premature death. Two common methods for estimating these costs are:

- Human Capital Approach: Values lost earnings due to morbidity or mortality

- Friction Cost Method: Considers only the short-term economic impact until a replacement is found

Intangible Costs

These include pain, suffering, and reduced quality of life. Though important, intangible costs are difficult to quantify and are often captured indirectly through utility measures in CUA (e.g., QALYs).

Measuring Health Outcomes (QALYs, DALYs)

Outcome measurement in economic evaluation must capture both length and quality of life. Two standard metrics are widely used:

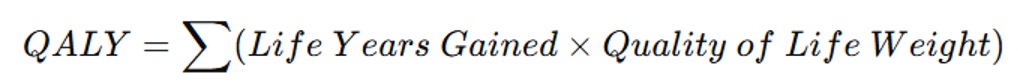

Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs)

QALYs combine survival and quality of life into a single measure. QALYs measure the additional years of life gained from a healthcare intervention, adjusted for quality of life. The formula for calculating QALYs is:

One QALY equals one year of life in perfect health. A health state with a utility weight of 0.5 for one year would generate 0.5 QALYs.

Utilities are derived from preference-based measures, often using instruments such as:

- EQ-5D

- SF-6D

- HUI (Health Utilities Index)

QALYs enable comparison across diseases and are central to cost-utility analysis.

Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs)

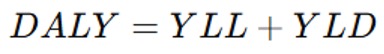

DALYs are used more often in global health and burden of disease studies. They represent the years of healthy life lost due to illness or premature death and are calculated as:

where YLL is Years of Life Lost, and YLD is Years Lived with Disability.

Unlike QALYs, DALYs focus on disease burden rather than preference-based valuations.

Applications of Economic Evaluation in Policy Decision-Making

Economic evaluation informs a wide array of policy decisions in health care, including:

Health Technology Assessment (HTA)

HTA agencies (e.g., NICE in the UK, CADTH in Canada) use economic evaluations to decide which drugs, devices, and interventions should be reimbursed. Cost-effectiveness evidence supports transparent, evidence-based coverage decisions.

Pricing and Reimbursement

Pharmaceutical pricing negotiations increasingly rely on value-based frameworks, where price is tied to the clinical and economic value demonstrated through CEA or CUA.

Program and Service Planning

Public health programs (e.g., vaccination campaigns, screening initiatives) are evaluated to determine their cost-effectiveness, aiding in resource allocation and budgeting.

Global Health and Development

Organizations like the WHO and World Bank use DALYs and CEA to prioritize investments in low- and middle-income countries, particularly for essential services in maternal health, infectious disease, and primary care.

Hospital and Provider Decision-Making

Hospital managers and providers apply economic evaluation to decide on service models, investment in new technologies, and quality improvement initiatives.

Conclusion

Economic evaluation provides an essential set of tools for making rational, evidence-informed decisions in health care. By systematically comparing the costs and outcomes of different interventions, economic evaluation supports efficient allocation of resources in the face of constrained budgets and competing priorities. Whether through BIA, CEA, CUA, or CBA, and whether considering QALYs, DALYs, or other metrics, these methods empower policymakers and health system stakeholders to maximize health outcomes while ensuring sustainability and equity.

References

- Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Claxton, K., Stoddart, G. L., & Torrance, G. W. (2015). Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Gold, M. R., Siegel, J. E., Russell, L. B., & Weinstein, M. C. (1996). Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Oxford University Press.

- Tan-Torres Edejer, T., et al. (2003). Making Choices in Health: WHO Guide to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. World Health Organization.

- Neumann, P. J., Sanders, G. D., Russell, L. B., Siegel, J. E., & Ganiats, T. G. (2016). Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Marsh, K., et al. (2017). Introduction to the Use of Health Economic Evaluation in Health Care Decision Making. Springer.